Beyond Funding Ratios: Five Ways to Assess the Health of Public Pensions

NCPERS Research Series: June 2023

Introduction

The purpose of this Research Series paper is to propose five ways, including a few innovative ones, to assess the health of public pensions. New assessment methods are desirable because current approaches are failing to deliver the reliable information on and insights into public pension funding that are needed to shape public policy.

The conventional way of gauging the health of pension plans is to analyze their long-term outlook by starting with a single point-in-time measure that is highly sensitive to the vagaries of the markets – that is, the funding ratio. In addition, much analysis takes funding levels out of context by comparing a pension fund’s long-term financial needs to the funds it has available in a single year. As a result, the magnitude of unfunded liabilities is distorted. It stands to reason that failing to factor in funding that will be collected over the long periods during which benefits are paid would warp the math.

Not surprisingly, these faulty approaches produce flawed analysis and recommendations. This is because they lean heavily on multiple unpredictable variables, in effect guessing at the direction that important factors such as interest rates, stock market performance, fiscal policy, and other variables will move over the course of decades. Yet policymakers routinely rely on such distorted assessments of public pension health as the basis for devising sweeping reforms. Doing so has long-lasting implications for public-sector workers and their beneficiaries. Over many years, policymakers have reduced public pension benefits, hiked employee contributions, and even closed plans to new hires on the basis of flawed and distorted analysis. We believe there are better, less damaging ways to evaluate the health and sustainability of public pension.

Low funding ratios are frequently an impetus for reforms.

A recent National Association of State Retirement Administrators (NASRA) pension reform brief notes:

… generally, plans that were more poorly funded enacted reforms that were more substantial than states that were better funded … One outcome of nearly all reforms passed during this period, however, is that public employees are responsible for an increasing share of funding of their retirement benefits and, in some cases, the accumulation of their own retirement assets.1

Similarly, a recent study by the Reason Foundation2 underscores low funding ratios as a driver of reforms but also enumerates other factors that may play a role:

-

Having higher funding ratios made states less likely to pass reforms.

-

Higher ratios of employer versus employee pension contributions made states more likely to pass reforms.

-

More populous states with larger public sectors tended to pass reforms.

-

States with more union members were less likely to pass reforms.

In addition to low funding ratios being the key driver of harmful pension reforms, the funding ratio is an incomplete measure. It measures the ratio of pension liabilities that are amortized over 30 years (or another amortization period) to the actuarial or market value of current assets instead of assets projected over the amortization period. For an apples-to-apples comparison, liabilities amortized over 30 years should be compared with the value of assets in the next 30 years as well.

Out-of-context comparisons of unfunded liabilities contribute to the push for harmful reforms.

Another argument that opponents of public pensions often use to push for harmful reforms is the unsustainable size of unfunded liabilities. They compare the magnitude of unfunded liabilities that are amortized over 30 years with annual revenues (or gross state product/economy). This is a highly misleading comparison. Unfunded liabilities that are amortized over 30 years should be assessed in the context of 30-year total revenues or economic output.

For example, a recent article in The Chicago Tribune argues that pension liabilities in Illinois are 1,000 percent of current annual state and local revenues.3 That figure certainly sounds terrifying, but it is the wrong comparison. When we compare pension liabilities that are amortized over 30 years, we need to compare them with total revenues that will be derived in the next 30 years. In such a comparison, unfunded liabilities in Illinois are only about 8 percent of revenues.4 The misleading argument that unfunded liabilities are 1,000 percent of state and local revenues is more likely to result in harmful reforms than is the factual argument that unfunded liabilities are only about 8 percent of revenues.

In a nutshell, we need to focus on measures that go beyond funding ratios to preserve public pensions.

Five ways to assess the health of public pensions beyond funding levels

We propose five ways to assess the health of public pension plans beyond funding levels:

-

Compare unfunded and total liabilities that are amortized over 30 years with the total economic capacity of the plan sponsor over the same period.

-

Assess the fiscal sustainability of the pension plan in terms of trends in the ratio between unfunded liabilities and the economic capacity of the plan sponsor.

-

Monitor the net amortization of the plan.

-

Monitor employers’ funding discipline.

-

Monitor trends in the fund-exhaustion period.

Let’s discuss each of these methods of assessment in turn.

1. Compare unfunded and total liabilities that are amortized over 30 years with the total economic capacity of the plan sponsor over the same period

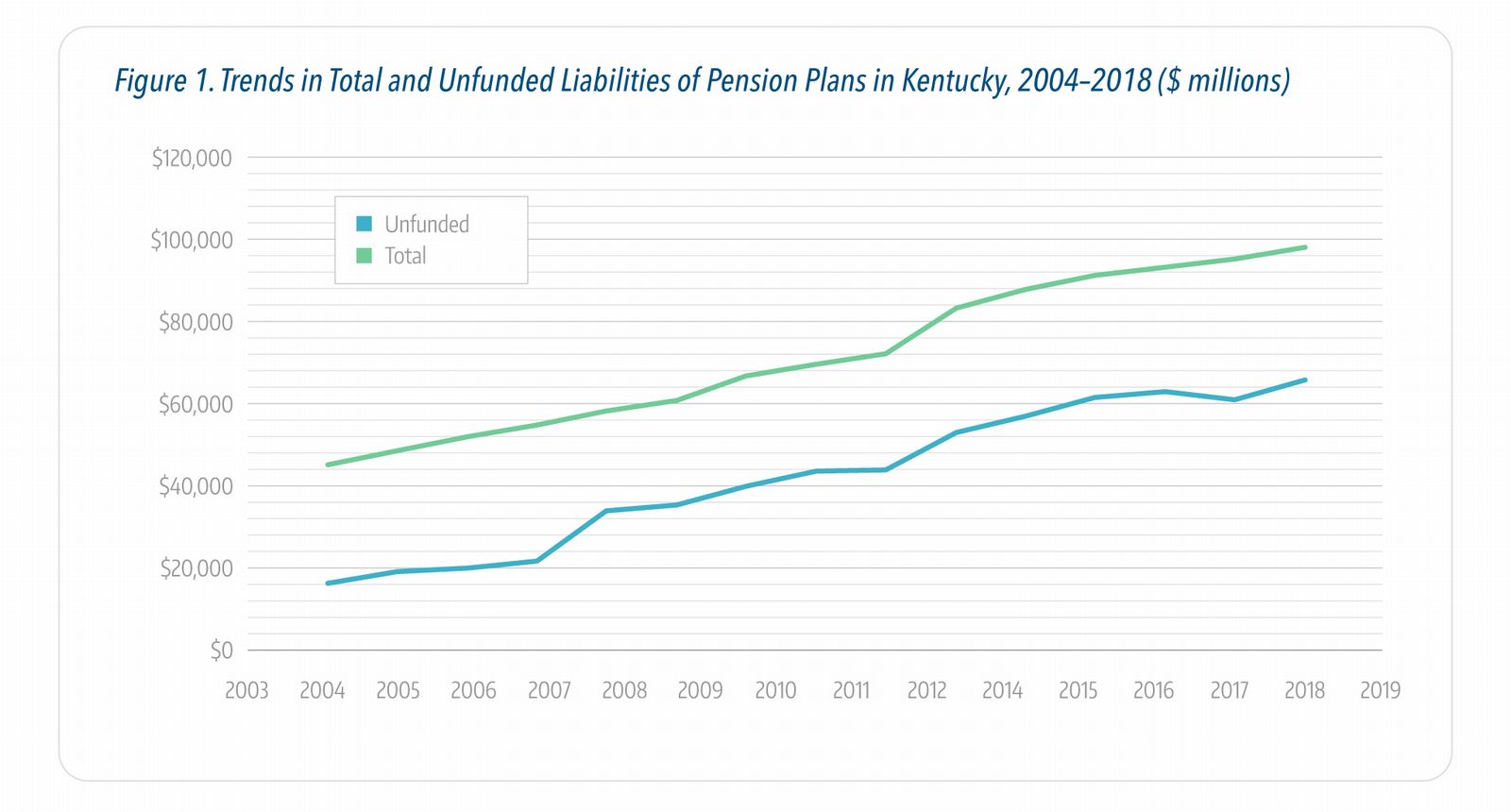

Too often, policymakers view unfunded and total liabilities of public pensions in isolation. Yet focusing simply on the trends in liabilities provides an incomplete picture, and that can lead to misguided decision making. If liabilities are rising rapidly, it’s easy to jump to the conclusion that their rise cannot be sustained. Therefore, the focus shifts to strategies such as cutting benefits, increasing employee contributions, or closing the pension plan to new hires. However, this is a one-sided view that overlooks other important facts. For example, while liabilities are growing, it’s very often the case that the economic capacity of the plan sponsors is also increasing. Liabilities must be considered in the context of the economic capacity of the plan sponsors.

Let’s look at the case of Kentucky – a state that often comes up in discussions of low funding ratios. Figure 1 shows the magnitude of total and unfunded liabilities from 2004 to 2018. The trend lines show a relatively steep upward trajectory, raising concern that these liabilities cannot be sustained, and something dramatic must be done.

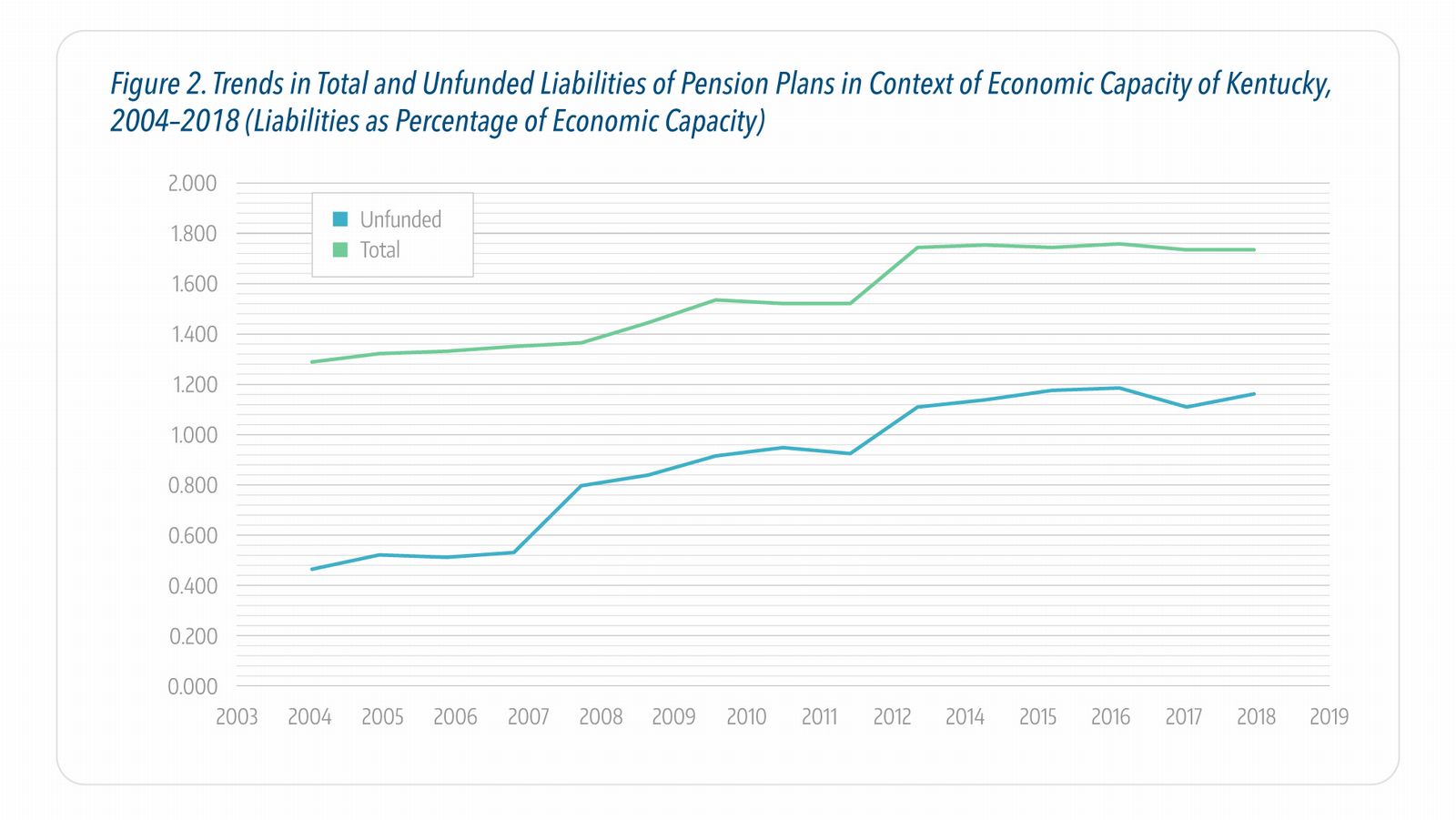

But if Kentucky policymakers had looked at trends in pension liabilities in the context of the state’s economic capacity, as shown in Figure 2, they would have found that liabilities were relatively stable or even declining, especially in recent years. In other words, Kentucky’s economic capacity, and thus the ability to afford its pensions, was stable or increasing faster than its liabilities.

Without considering the measure shown in Figure 2 when examining the health of public pensions, policymakers could easily be misled by focusing on the size of unfunded liabilities and comparing them with annual revenues or the size of the economy. For example, Kentucky’s unfunded pension plan liabilities were $65.6 billion in 2018, according to Federal Reserve data.5 During the same year, state and local revenues in Kentucky amounted to $33.2 billion, according to Census Bureau data.6 But does that mean that the unfunded liabilities of Kentucky pension plans were 200 percent of annual revenues, justifying radical reform? Of course that is not what the data suggest.

The problem with the comparison is that it sizes up unfunded liabilities, which are amortized over 30 years, against a single year’s revenue. For an accurate assessment, we must compare unfunded liabilities with Kentucky’s revenue over the next 30 years, which will be almost $1 trillion, assuming no growth. This means unfunded liabilities are only about 6.5 percent of available revenues. Similarly, total economic output in Kentucky during the period over which the $65.6 billion in unfunded liabilities is amortized (or to be paid off) would be about $5.6 trillion. In other words, unfunded liabilities will represent about 1.2 percent of Kentucky’s economy over the amortization period. This is hardly a “sky is falling” scenario that warrants extreme measures such as closing pension plans to new hires.

2. Assess the fiscal sustainability of the pension plan in terms of trends in the ratio between unfunded liabilities and the economic capacity of the plan sponsor.

Some people are ideologically opposed to public pensions. Their bias is to focus on the magnitude of unfunded liabilities and declare that public pensions are unsustainable. Their error is that they are not evaluating unfunded liabilities in the context of the economic capacity of the plan sponsor. True unfunded liabilities may indeed be increasing – but so is the plan sponsor’s economic capital to support a pension plan. Unfunded liabilities must be considered in the context of the economic capacity of the plan sponsor in order to accurately assess a pension plan’s sustainability.

Fiscal sustainability is a well-established concept in economics. It means that the ratio of debt to economic capacity is stable or declining over time. It’s a simple concept that applies to all of us as individuals as well. For example, if our debt and income are rising in concert, we can sustain our debt. But if our debt is rising faster than our income, we cannot sustain it.

The concept of fiscal sustainability also applies to public pensions. If unfunded pension liabilities continue to rise faster than the economic capacity of the plan sponsor, liabilities are likely to become unsustainable. However, if they are rising more slowly or in concert with the economic capacity of the plan sponsor, the pension plan is sustainable. Monitoring the ratio of unfunded liabilities to the plan sponsor’s economic capacity against a benchmark – such as the historical average or another benchmark – can be a powerful tool in assessing and managing the health of a pension plan.

The NCPERS study Enhancing Sustainability of Public Pensions applies the concept of fiscal sustainability to state and local pension plans in each state.7 The study refers to the application of the concept of fiscal sustainability to public pensions as the “sustainability valuation.” Let’s look at the sustainability valuation of pension plans in New Jersey – another state that comes up in discussions of states with low funding ratios.

Figure 3 compares unfunded liabilities for New Jersey’s state and local pension plans, amortized over 30 years, to the economic capacity of New Jersey’s state and local governments during the same period. The trend line is plotted against a benchmark, the average ratio from 2004 to 2018 in New Jersey; of course, it is possible to choose another benchmark such as the current value of the ratio. The goal of prudent policy should be to monitor and stabilize the ratio trend line at or below the benchmark.

In addition to monitoring the ratio trend line, the sustainability valuation approach allows us to estimate the changes needed to stabilize the trend line at the benchmark. In the case of New Jersey, if unfunded liabilities in 2018 had been about 0.9 percent lower than they were, state and local pension plans in New Jersey would have been fiscally sustainable.

An analysis of the 50 states in the NCPERS study shows that using the sustainability valuation – stabilizing the ratio of unfunded liabilities to the plan sponsor’s economic capacity – has several benefits:

-

The sustainability valuation shifts the focus from cutting benefits and closing plans to stabilizing unfunded liabilities in relation to economic capacity.

-

As unfunded liabilities stabilize, funding levels are likely to improve.

-

At the same time, contribution rates, measured as a percentage of revenues, are likely to decline.

-

The sustainability valuation gives plan sponsors and policymakers important information that they can use to prevent a well-funded plan from becoming unsustainable due to changes in the sponsor’s economic circumstances.

It is important to note that the sustainability valuation is one more tool that can be used to assess and manage pension plans. It does not replace the value of existing tools, including actuarial valuation, plan sponsors’ funding discipline, stress testing, and sound investment policies.

3. Monitor the net amortization of the plan.

Net amortization is a way of measuring whether the annual contribution rate reduces or increases unfunded liabilities, presuming all other assumptions are met. The contribution rate may result in negative or positive amortization. If the annual contribution rate decreases liabilities, its impact is referred to as positive amortization. If, in contrast, liabilities increase despite contributions, the result is negative amortization. A 2017 study by the National League of Cities underscores the importance of monitoring net amortization to assess the health of a public pension plan.8 A recent Pew Charitable Trusts study shows that net amortization was negative in 15 states in 2019.9 In other words, even if these states were making annual contributions, their unfunded liabilities went up. Kenneth Kriz of the University of Illinois notes that special attention should be paid to appropriate rate of return in determining amortization.10

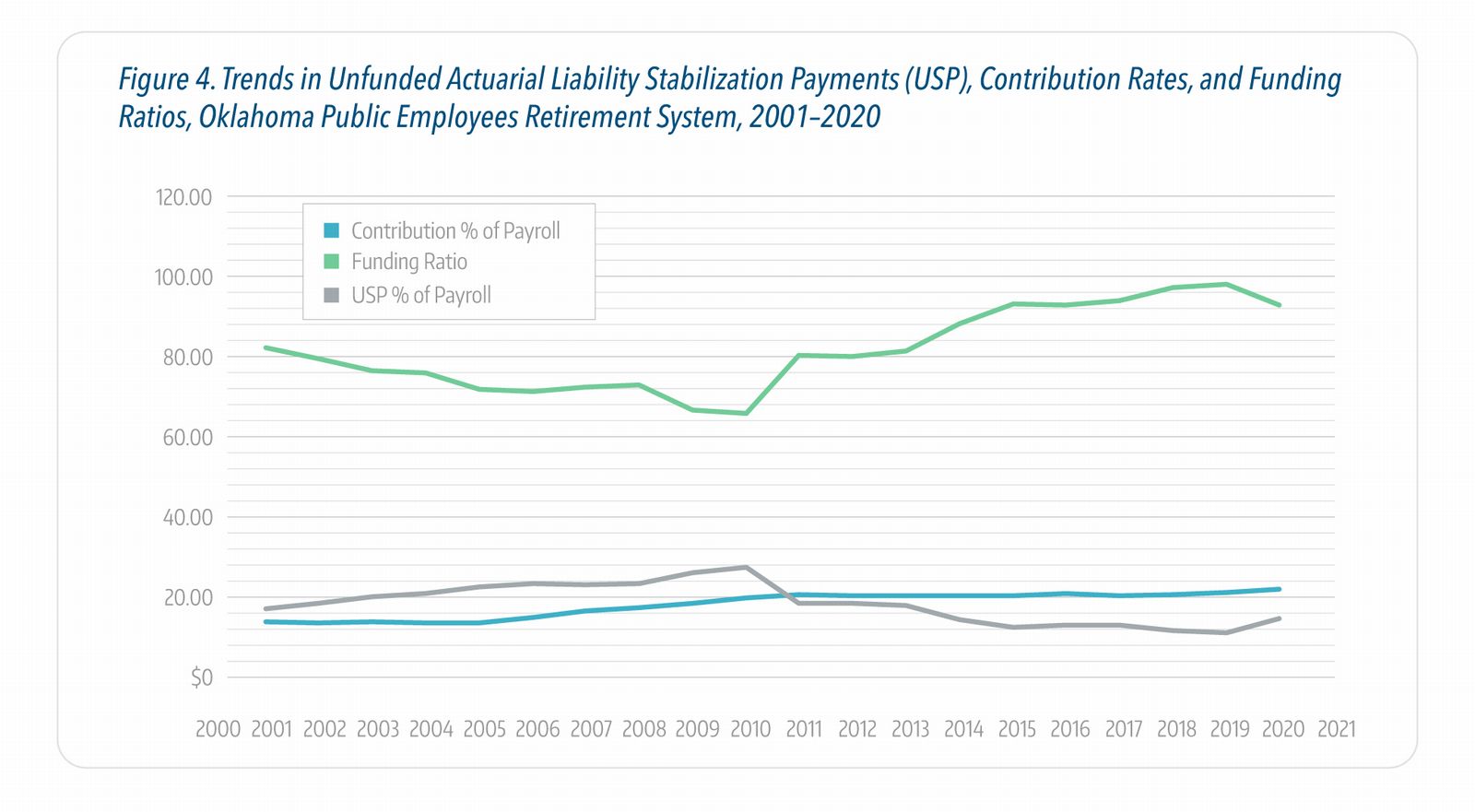

If amortization continues to be negative, there are solutions that can be considered. A 2022 NCPERS publication authored by Tom Sgouros of Brown University proposes that an effort should be made to stabilize unfunded liability through unfunded actuarial liability (UAL) stabilization payments, or USPs.11 The USP is the payment necessary to leave a plan in the same condition at the end of a year as it was at the beginning, presuming all other assumptions are met. Details on how to calculate the USP are shown in the report, Measuring Public Pension Health: New Metrics and New Approaches. This approach can have a significant impact on the health of a pension plan. The study illustrates this using the example of the Oklahoma Public Employees Retirement System.

Figure 4, borrowed from the NCPERS publication, shows that during the period that contributions to the Oklahoma Public Employees Retirement System were below the USP, from 2000 through 2010, the system saw a steady decline in the funding ratio. In 2010, the USP decreased, largely through a substantial decline in service costs, to a level below the annual contributions. As a result, the funding ratio began to climb.

4. Monitor employers' funding discipline.

If employers skip a contribution or pay less than the actuarially determined contribution (ADC), it throws everything off balance. It’s hard to make up the loss created by skipping the contribution or paying less than is required. This is because the asset base that grows through a compound rate of return on investments continues to be smaller. Pension plan managers should monitor contributions closely and press for employers to pay 100 percent of their ADC.

A study by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College shows that pension plans in which plan sponsors skipped or underpaid their required pension contributions had relatively low funding ratios.12 Conversely, a study by the National Institute on Retirement Security found that pension plans in which plan sponsors made the full required contribution were well funded and remained well funded through the 2001 and 2007–2008 recessions.13

The NCPERS study, which takes into account various factors in determining the fiscal sustainability of public pensions, found that for each 1.00 percent of additional contribution closer to ADC, funding levels improve by 0.23 percent.

In short, it is important to assess funding discipline – that is, the habit of always making the full required contribution – in the past as well as going forward. As various studies show, funding discipline has a profound impact on the health of a pension plan.

5. Monitor trends in the fund-exhaustion period.

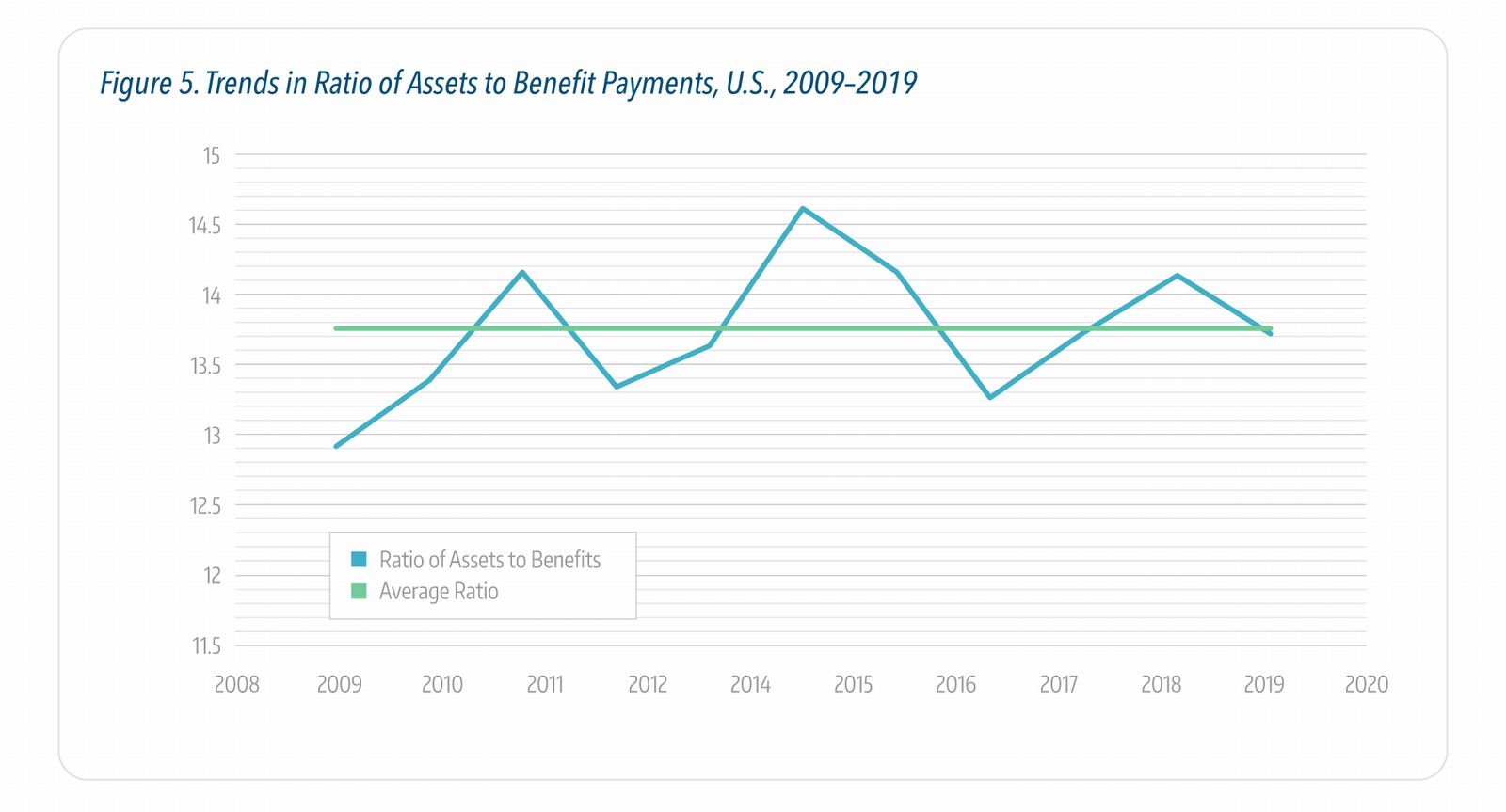

In actuarial terms, the fund-exhaustion period is the point in time at which a pension fund would no longer be able to pay benefits if assets were frozen at current levels. A rough way to look at the fund-exhaustion date is by simply considering the ratio of current assets to annual benefit payments. For example, the average ratio of assets to annual benefit payments over a recent 10-year period (2009 to 2019, the latest years for which data are available) is about 13.7. This means that if everything were frozen, state and local pension plans could pay benefits for the next 13.7 years.

Figure 5 shows how the ratio of assets to benefit payments fluctuated during the decade in relation to the average ratio. It also shows that there was an improvement in the financial health of state and local pension plans from 2009 to 2019. For example, in 2009 state and local pension plans had enough assets to pay benefits for about 12.8 years. The figure for 2019 was 13.8 years.

There are more sophisticated methods to estimate the fund-exhaustion period, which involve projections of assets, contributions, and benefit payments. But the simple calculation is something that trustees can do on the back of an envelope and get a sense of the direction in which the financial health of the plan is moving. For example, if in 2021 the depletion date of a plan is 2026, that is serious. But if in 2022 the depletion date has also advanced a year to 2027, that suggests the situation is stable, not deteriorating. Using the fund-exhaustion period to assess the health of a pension plan is especially important for plans that are projected to run out of money in a few years.

Conclusion

Opponents of public pensions often make the case to policymakers that funding ratios are too low and unfunded liabilities are too high. They often compare the size of unfunded liabilities, which are usually amortized over 30 years or so, with annual revenues. They then argue that unfunded liabilities are too high and the pension plan is unsustainable, and therefore should be converted into a do-it-yourself retirement savings plan such as a 401(k)-type defined contribution plan, especially for new hires. However, an apples-to-apples comparison requires that unfunded liabilities be evaluated against total revenues collected over the amortization period.

Opponents of public pensions also fail to consider the economic strength of the jurisdiction in which the pension plan is located. While it might not be the ideal option, state and local governments are entirely capable of maintaining pensions on a pay-as-you-go basis. Prefunding of pension plans simply makes the pension plan less expensive for taxpayers because two-thirds of the funding generally comes from return on investments. In assessing the health of a pension plan, we must keep in mind the economic strength of the plan sponsor.

We have proposed five ways to assess the health of public pension plans that go beyond funding ratios and calculations based on a faulty understanding of the magnitude of unfunded liabilities. We believe these approaches can help policymakers to gain a clean, clear, and true picture of the health of pension plans.

The stakes are high. Continuing to tinker with pension benefits jeopardizes the ability of our cities, counties, and states to deliver needed services by undermining their ability to attract high-caliber public-sector employees. Making these changes when there are alternatives is extremely shortsighted. Adopting new approaches to assessing pension plan health can help dissuade policymakers from turning to radical reforms for short-term solutions that, unfortunately, undermine public pensions in the long run.

Acknowledgments:

This research series was written by Michael Kahn, PhD, Director of Research at NCPERS. The author and NCPERS are grateful to Professor Kenneth Kriz of the University of Illinois and Research Professor Tom Sgouros of Brown University for their valuable comments on an earlier draft of this Research Series paper.

Sources:

1 Keith Brainard and Alex Brown, Spotlight on Significant Reforms to State Retirement Systems (Lexington, KY: National Association of State Retirement Administrators, 2018), 6.

2 Michael Bednarczuk and Jen Sidorova, Determinants of Public Pension Reform (Los Angeles: Reason Foundation, 2021).

3 Mark Glennon, “Commentary: The Path to Illinois Pension Reform,” Chicago Tribune, September 1, 2020.

4 Author’s calculations.

5 Federal Reserve Board, State and Local Pension Funding Status and Ratios by State, 2002–2020, last updated December 16, 2022.

6 Urban Institute, State and Local Finance Data, accessed April 2022.

7 Michael Kahn, Enhancing Sustainability of Public Pensions (Washington, DC: NCPERS, 2022).

8 Anita Yadavalli, How to Measure Pension Fiscal Health: Municipal Action Guide (Washington, DC: National League of Cities, 2017).

9 Pew Charitable Trusts, Pew’s Fiscal Sustainability Matrix Helps States Assess Pension Health (Philadelphia: Pew Charitable Trusts, 2021).

10 E-mail exchange with Professor Kriz, University of Illinois, Springfield.

11 Tom Sgouros, Measuring Public Pension Health: New Metrics and New Approaches (Washington, DC: NCPERS, 2022).

12 Alicia H. Munnell, Jean-Pierre Aubry, and Laura Quinby, “The Impact of Public Pensions on State and Local Budgets,” Issue in Brief 13 (Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, 2010).

13 Jun Peng and Ilana Boivie, Lessons from Well-Funded Public Pensions: An Analysis of Six Plans that Weathered the Financial Storm (Washington, DC: National Institute on Retirement Security, 2011).